Network-level validation

Modeling and the simulation of the activity in neuronal networks is an essential part of modern neuroscience and represents a powerful vehicle to combine insights from experiments and theory into a coherent understanding of brain function.

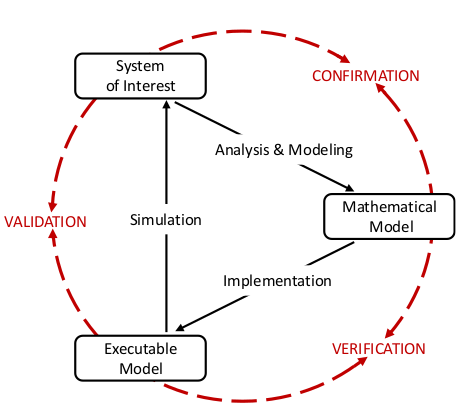

The only measure to assess how much trust we can place in a given model is how well it can predict the biological reality it aims to describe. Validation testing formalizes the comparison between measured and simulated data and quantifies their similarity. The resulting test scores characterize the model and determine its validity with respect to predictions concerning the experimental reference. However, it is sometimes useful to directly compare two models by means analogous to validation testing. Such direct comparisons are not constrained by the scarcity and specificity of experimental data and thus allow for more thorough evaluation of the two models. In contrast to validation, direct comparisons between two models are not able to determine the descriptive power of a model regarding its reference to reality. They can, however, be greatly beneficial in evaluating the model’s consistency, robustness with respect to parameter variation, and directed improvements in the model development process.

In either scenario, several aspects must be considered. Any validation test only considers a specific statistic of a certain aspect of a finitely sampled data set. Therefore, in order to gain a more complete and less biased evaluation, it is necessary to apply multiple validation tests, taking into account different aspects and statistical measures. For example, for a neural network model the dynamics on the single-cell and network activity level are not trivially related, and thus should be regarded individually. Additionally, any test score should be quantitative, reproducible, and ideally based on open, standardized software tools.

Modeling and the simulation of the activity in neuronal networks is an essential part of modern neuroscience and represents a powerful vehicle to combine insights from experiments and theory into a coherent understanding of brain function.

The only measure to assess how much trust we can place in a given model is how well it can predict the biological reality it aims to describe. Validation testing formalizes the comparison between measured and simulated data and quantifies their similarity. The resulting test scores characterize the model and determine its validity with respect to predictions concerning the experimental reference. However, it is sometimes useful to directly compare two models by means analogous to validation testing. Such direct comparisons are not constrained by the scarcity and specificity of experimental data and thus allow for more thorough evaluation of the two models. In contrast to validation, direct comparisons between two models are not able to determine the descriptive power of a model regarding its reference to reality. They can, however, be greatly beneficial in evaluating the model’s consistency, robustness with respect to parameter variation, and directed improvements in the model development process.

In either scenario, several aspects must be considered. Any validation test only considers a specific statistic of a certain aspect of a finitely sampled data set. Therefore, in order to gain a more complete and less biased evaluation, it is necessary to apply multiple validation tests, taking into account different aspects and statistical measures. For example, for a neural network model the dynamics on the single-cell and network activity level are not trivially related, and thus should be regarded individually. Additionally, any test score should be quantitative, reproducible, and ideally based on open, standardized software tools.

- Python package NetworkUnit

- Talk

- Validation paper

- Verification paper

- latest Poster

Related tags: Validation

Collaborative Brain Wave Analysis Pipeline

In the past decades, neuroscience excelled at accumulating a rich, heterogeneous landscape of datasets and methodologies. It poses, however, a new challenge to effectively leverage the benefits of such diversity by combining the insights from across experiments, studied species, and measurement techniques in order to build a cumulative understanding of brain function.

Integration of this heterogeneity requires rigorous analysis workflows that offer to distill consistent, reproducible, comparable, and reusable conclusions. Aligning data from various sources enables not only “big-data” analysis approaches, but also allows to produce a broader experimental basis for validating models and theories across the experimental and computational scales of description.

I explore this approach in the context of cortical wave activity, which is persistently observed in across various species, measurement techniques, and brain states. In particular, slow wave activity (1-5 Hz) is ubiquitous during sleep and anesthesia, and beta waves are prominent in the motor cortex during movement planning.

The Collaborative Wave Analysis Pipeline (Cobrawap) is a framework of modular elements that makes it possible to adapt analysis workflows to diverse data modalities and derive comparable characterizations of wave activity. Here, the key objective is to interface existing methods, standards, and tools in a flexible manner in order to serve the requirements of a wide range of datasets and research questions using a common set of analysis components. Moreover, by building on and co-developing other specialized open-source tools, I further emphasize the reusability and extendability of each of the pipeline components.

To demonstrate the pipeline I perform "meta-studies" of wave characteristics (such as velocities or directions) across a range of openly available ECoG and calcium imaging datasets and investigate the influences of experimental parameters such as the mice’s genetic strain, the type and dosage of anesthetics, the measurement technique and the spatial resolution. Further the pipeline can also be used to benchmark

specific methods within the analysis by switching them with another method and analyzing the same pool of data. Finally, its reusable design and modularity helps to derive other analysis pipelines for similar research endeavors to amplify collaborative research.

In the past decades, neuroscience excelled at accumulating a rich, heterogeneous landscape of datasets and methodologies. It poses, however, a new challenge to effectively leverage the benefits of such diversity by combining the insights from across experiments, studied species, and measurement techniques in order to build a cumulative understanding of brain function.

Integration of this heterogeneity requires rigorous analysis workflows that offer to distill consistent, reproducible, comparable, and reusable conclusions. Aligning data from various sources enables not only “big-data” analysis approaches, but also allows to produce a broader experimental basis for validating models and theories across the experimental and computational scales of description.

I explore this approach in the context of cortical wave activity, which is persistently observed in across various species, measurement techniques, and brain states. In particular, slow wave activity (1-5 Hz) is ubiquitous during sleep and anesthesia, and beta waves are prominent in the motor cortex during movement planning.

The Collaborative Wave Analysis Pipeline (Cobrawap) is a framework of modular elements that makes it possible to adapt analysis workflows to diverse data modalities and derive comparable characterizations of wave activity. Here, the key objective is to interface existing methods, standards, and tools in a flexible manner in order to serve the requirements of a wide range of datasets and research questions using a common set of analysis components. Moreover, by building on and co-developing other specialized open-source tools, I further emphasize the reusability and extendability of each of the pipeline components.

To demonstrate the pipeline I perform "meta-studies" of wave characteristics (such as velocities or directions) across a range of openly available ECoG and calcium imaging datasets and investigate the influences of experimental parameters such as the mice’s genetic strain, the type and dosage of anesthetics, the measurement technique and the spatial resolution. Further the pipeline can also be used to benchmark

specific methods within the analysis by switching them with another method and analyzing the same pool of data. Finally, its reusable design and modularity helps to derive other analysis pipelines for similar research endeavors to amplify collaborative research.

Eigenangles

Neural systems can be represented as networks, where neurons constitute the nodes and the connection between pairs of neurons is given by either the synaptic strength or functional connectivity, as given for example by the correlations of spiking activity.

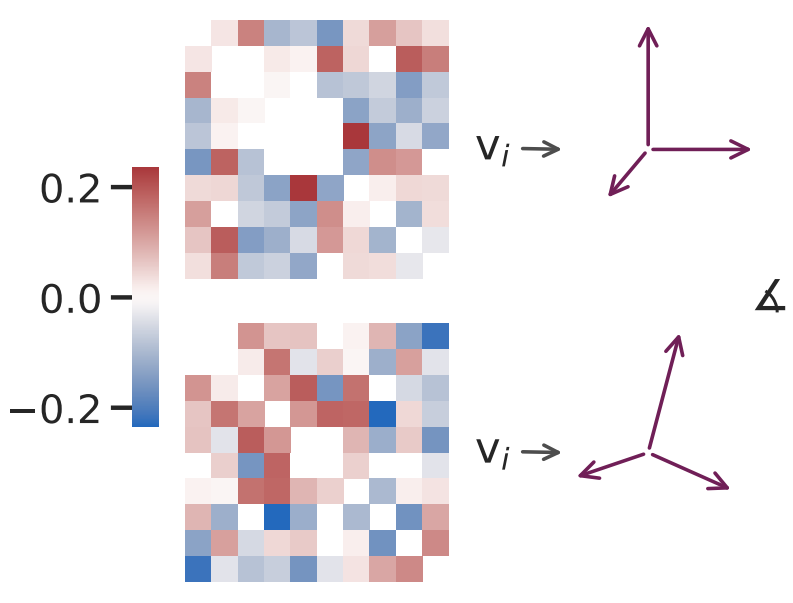

Performing quantitative comparisons between different networks is a prevalent task in many research scenarios. Overcoming the some limitations of just comparing the one dimensional distributions of characteristic measures, I constructed a statistical test for the

comparison of matrices representing pairwise aspects of neural networks, in particular the correlation of spiking activity and the anatomical connectivity.

The "eigenangle test" quantifies the similarity of two matrices by the angles between their ranked eigenvectors. Applying the test to correlation matrices of stochastic models of correlated spiking activity it demonstrates how it can detect structural aspects of the correlation (e.g., correlated assemblies) that is not visible for classical two-sample tests.

Furthermore, the principle of the eigenangle test can be applied to compare the similarity of adjacency matrices of certain types of networks. Thus, the approach can be used to quantitatively explore the relationship between connectivity and activity with the same metric. By applying the eigenangle test to the comparison of connectivity matrices and correlation matrices of a random balanced network model before and after a specific synaptic rewiring intervention, it becomes possible to gauge the influence of connectivity features onto the correlated activity of the network. Potential applications of the eigenangle test include simulation experiments, model validation, and data analysis.

Neural systems can be represented as networks, where neurons constitute the nodes and the connection between pairs of neurons is given by either the synaptic strength or functional connectivity, as given for example by the correlations of spiking activity.

Performing quantitative comparisons between different networks is a prevalent task in many research scenarios. Overcoming the some limitations of just comparing the one dimensional distributions of characteristic measures, I constructed a statistical test for the

comparison of matrices representing pairwise aspects of neural networks, in particular the correlation of spiking activity and the anatomical connectivity.

The "eigenangle test" quantifies the similarity of two matrices by the angles between their ranked eigenvectors. Applying the test to correlation matrices of stochastic models of correlated spiking activity it demonstrates how it can detect structural aspects of the correlation (e.g., correlated assemblies) that is not visible for classical two-sample tests.

Furthermore, the principle of the eigenangle test can be applied to compare the similarity of adjacency matrices of certain types of networks. Thus, the approach can be used to quantitatively explore the relationship between connectivity and activity with the same metric. By applying the eigenangle test to the comparison of connectivity matrices and correlation matrices of a random balanced network model before and after a specific synaptic rewiring intervention, it becomes possible to gauge the influence of connectivity features onto the correlated activity of the network. Potential applications of the eigenangle test include simulation experiments, model validation, and data analysis.

- Python implementation of Eigenangles

- Paper

- latest Poster

Neuro Pottery

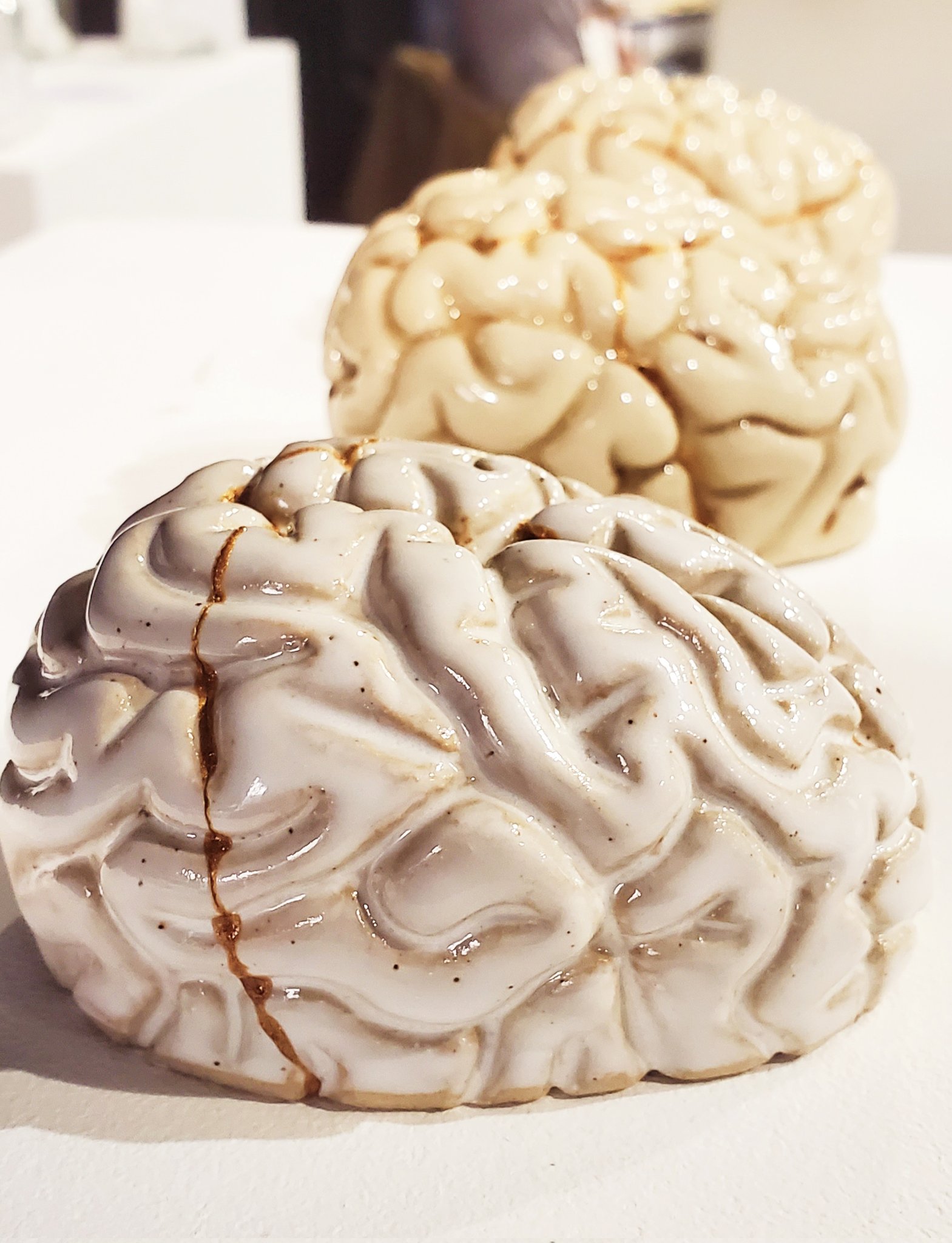

Art and science can interact a symbiotic relationship. Scientific topics are often a sources for compelling art pieces; and art can as a creative approach to address scientific questions in thought provoking ways. There are many efforts that promote "SciArt", and "BrainArt" (or "NeuroArt") in particular. One of them is the OHBM BrainArt exhibition, that is organized as a part of the annual OHBM (Organization for Human Brain Mapping) conference. In this context, I presented the piece "The kintsugi brain".

Art and science can interact a symbiotic relationship. Scientific topics are often a sources for compelling art pieces; and art can as a creative approach to address scientific questions in thought provoking ways. There are many efforts that promote "SciArt", and "BrainArt" (or "NeuroArt") in particular. One of them is the OHBM BrainArt exhibition, that is organized as a part of the annual OHBM (Organization for Human Brain Mapping) conference. In this context, I presented the piece "The kintsugi brain".

"This artwork is inspired by the brain's plasticity. The brain can rewire and repair its broken connections. Kintsugi is the Japanese art of repairing broken bowls or other pottery with gold, highlighting its cracks, and celebrating its imperfections as part of its history. Initially, plasticity allows for molding the clay and for molding the brain in its early development by the external influences imposed on it. Once in its apparent final shape, it is still subject to change and external forces. Bowls can break. Brains can break. Plasticity does not end. In many cases, they can still be repaired and become more valuable in the process. The philosophy of kintsugi, thus, raises the question: how much do we gain from our scars? And in which way is the brain entirely unlike a bowl?"

Dynamics of cortical LFP waves and spikes

[to be filled]