When working with model simulations and their evaluation, it is important to be clear about the used terminology and interpretation of the results. Otherwise, gaining insights from the model would be basically a game of chance. While learning something new via modeling is an alluring approach, one might first consider whether or not it is at all possible to gain new knowledge or truth from models. This question is matter of ongoing philosophical debate (Oreskes et al., 1994; David, 2009; Irobi et al., 2004), but fortunately the gaining of new knowledge is not what validation is about. And while the epistemologists are working out the details, for the practical approach of modeling we should not be concerned with the truth content of a model but with its testable correctness. Because only the model’s accuracy relative to the given system justifies its use as the basis for analytic argumentation and prediction making. Establishing the absolute validity of a model is inherently impossible, as a model is by design an abstraction and simplification of reality (Balci, 1997; Sterman, 2000). There are multiple aspects in evaluating a model, but a validation is a major part of it as it describes the process of assigning credibility to a model. Validation within its logic of inductive reasoning is not able to infer any certain statement. This problem was most famously addressed by the philosopher David Hume in 1748. Thus, the outcome of a validation should not be understood as a definite verdict about its validity but as an quantitative evaluation of usefulness. This usefulness may commonly be given in the form of probability values which are based on observed evidence and a priori assumptions and beliefs (Carnap, 1968).

Such quantification of usefulness can also be understood as the level of trust we place in a model. Think about two very common models:

There is the much trusted standard model in particle physics which is able to make immensely precise predictions which have been confirmed over and over again (most recently by the Higgs-Boson, and gravitational waves) and is probably the best model there is. This is why any violation of its predictions is likely related to groundbreaking new physics. However, we can be design not claim that the model is true in that sense, just that it is immensely useful.

On the other hand there are very sophisticated meteorologic models which are also able to make very useful predictions, but as you know, every once in a while, the weather forecast proves to be wrong. Therefore, we wouldn’t place as much trust in its predictions, i.e., it has a lesser level of usefulness (while acknowledging that we are comparing apples and chaotic oranges here).

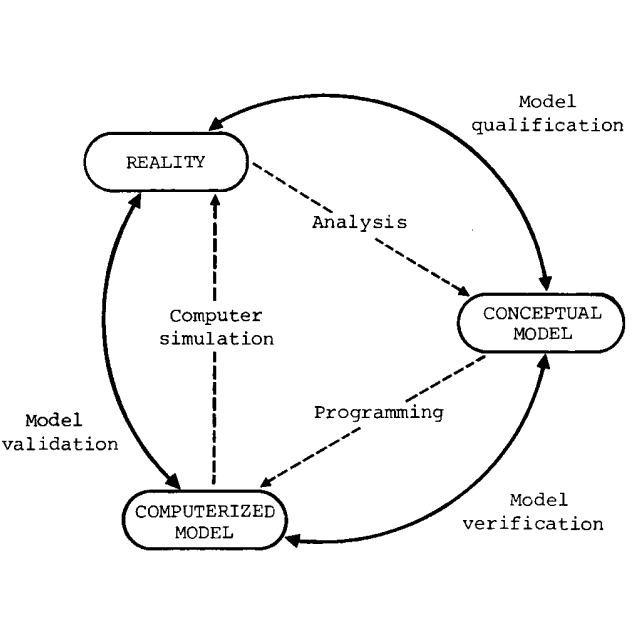

In 1979 the Technical Committee on Model Credibility of the Society of Computer Simulation established a simple and widely used description of a simulation environment which is separated into three basic elements, as shown in the Figure below. The model itself is separated into the conceptual model and the computerized model or simulation. The conceptual model is an abstract description (for example in the form of mathematical equations) formed by analysis of, and assumptions about the reality interest. The reality of interest (sometimes also called problem entity) can be defined as “an entity, situation, or system which has been selected for analysis” (Schlesinger, 1979). When specifying this reality of interest it is important to also explicitly define the boundaries in which the modeling is expected to be adequate.

The assessment of the quality of the conceptual model and testing if the modeling is done in a formally correct manner is performed in a process termed qualification. Equivalent names, also found in the literature, are confirmation and conceptual validation. This means that the process towards the enhancement of the credibility of a conceptual model does not solely rely on computerization and simulation. Rather, in the qualification step the model has to also oblige to a range of simulation independent criteria as they were, for example, specified by Khazanchi (1996):

Plausibility: A plausible model incorporates a correct inductive logic and

a reasonable input-output relationship which sets it apart from simple beliefs

or conjectures.

Feasibility: Feasibility demands that the conceptual model is

operationalizable in a way that it is amenable to characterization.

Effectiveness: In addition to describing the reality of interest the

conceptual model has the potential to serve a scientific purpose.

Pragmatism: Conceptual models should not logically exclude previously valid

concepts and have some degree of abstract, logical self-consistency or coherence

with other concepts in the discipline.

Empirical content: This criterion demands the empirical testability of the

conceptual model. “Elaboration by reasoning may make a suggested idea very rich

and very plausible, but it will not settle the validity of that idea”

(Dewey, 1933).

Predictiveness: A key criterion for the usefulness a conceptual model is

its ability to predict facts that have not yet been observed.

Inter-subject certifiability: Different investigators must be able assert

the credibility of the conceptual model through observation, logical

evaluation, or experimentation.

Inter-methodologically certifability: The conceptual model must be testable

by different research methodologies which should also conclude the same

predictions.

An implementation of the conceptual model in a computer software or hardware

results in a computerized model. The process of checking if this transition is

not flawed in any way and the computerized model is a correct representation of

the conceptual model is named verification. The comparison of the computerized

model to the reality of interest is the process called validation, or more

precisely, operational validation to emphasize that it is the validation of the

simulation and not of the conceptual model. The term validation is often used

very laxly, but here I will make an effort to use a precise terminology.

As the terms verification, qualification, and validation are used to

distinguish the comparisons between the different elements in the framework of

model development they also associate with different degrees of possible

confidence. Verification is the strongest as it, if successful, guarantees

certainty. The implementation of the conceptual model in a computerized model

can be absolutely accurate representation of the model in terms of the

understanding of the modeler (i.e, it is logically true). The qualification of

the conceptual model in relation to its reality of interest does not aim at

truth but at plausibility or probability given the evidence. The

validation of the simulation/computerized model against the reality, on the other

hand, aims at providing confidence that the model is consistent with observations

and non-contradicting. (Oreskes et al., 1994)

This distinction is very relevant in order to adequately perform and interpret

the verification, qualification, validation steps and to establish an awareness

of what can and cannot be achieved by those processes. Since the publication of

this rather simple view of the validation process in 1979, many derived diagrams

have been employed which emphasize additional aspects, for example, the

uncertainties in experiments and simulation and their quantification. Other,

more complex diagrams point out that model validation is an ongoing and

iterative process within a larger workflow of modeling and experimentation

(Murray-Smith, 2015). Another notable extension is the explicit inclusion of the

validation of experimental data (Sargent, 2013). Both the model building process

and the validation of the computerized model rely on experimental data. This

data needs to be adequate and correct, to ensure that the validation testing can

be actually meaningful.

Since we here focuses not on the conceptual modeling but on the simulation,

the major interest lies in the verification and validation process (termed V&V

for short) as opposed to the model qualification. There exist multiple

definitions in the literature for the terms verification and validation. The

most prominent definitions are depicted in the table at the end of the post. Despite some discrepancies

in the definitions (e.g. the definition by Giannasi et al. (2001) could also be

used for qualification), they agree on the essential aspects. One key element of

these definitions is the distinction that verification tests the correctness of

the implementation of the conceptual model into a computerized model and

validation quantifies the accuracy of this computerized model with respect to

the related reality. Consequently, a validation can never be conclusive but the

more validation tests are performed, the better the credibility of the model can

be assessed and the more confidence may be placed into the model.

There is not a single test that is sufficient for a model to be validated

(Forrester & Senge, 1980).

Generally, there is also no standard way how to validate. There exists a large

variety of tests and methods, and the choice which one to apply always has to be

adapted to the model, its intended use, the nature of the data, and the

corresponding reality of interest. However, there have been efforts to group

them into phases and generalize common test schemes. Forrester & Senge (1980)

classified a range of validation tests into three phases:

Structure: This phase contains tests which primarily focus at structural

aspects of the model such as its dimensions, extreme-conditions and boundaries.

They pose questions like if its parameters have real system equivalents or if

its complexity is appropriate for the subject of study and its intended use.

Behavior: Tests of this phase investigate the adequacy of the model through

its behavior. Examples for typical test questions are: Can the model predict

future behavior? Can the model reproduce historical findings? Does the model show

surprising and unexpected behaviors? How sensitive is the model to plausible

shifts in the model parameters? Does it behave as expected under extreme

conditions? Does the model behavior have the same statistical properties as

the real system?

Policy Implications: Tests of policy implications attempt to check if the

response of the real system to a policy change corresponds to the response

predicted by the model when its policy is changed accordingly.

Martis (2006) further introduced subgroups which can subdivide the typical

validation tests in each of the three phases on the basis of their focus towards

the model’s suitability, consistency, and utility and effectiveness.

Notable about this general validation scheme is that not all validation tests are

based on a direct comparison of the simulation to empirical data. As indicated by

the above points, a lot of the validation process can be already done by performing tests regarding very basic, either explicit or implicit features of the reality of interest, such as the ’feature’ of internal consistency. Such test may also perform comparisons to other already established models.

Validation and verification of models and simulations are used with this terminology in a variety of diverse fields. Within each field the rigorous procedure of V&V is vital to the model development process for which a precise terminology is essential. However, also across fields a consistent terminology is important. Only this can enable modelers, scientists, and philosophers to uncover and discuss mismatches in use and interpretation of validation methods. Since the evaluation of model credibility is a highly non-trivial process with many logical and practical pitfalls, and as we rely heavily on the information we infer from models and their simulation, we have to be aware of the level of confidence we can put in these information and how to gain an adequate amount of confidence.

This is especially true in the field of neuroscience. Neuroscience is in the special position to have a relatively difficult access to experimental data. Experiments recording brain activity are naturally subject to strict regulations, especially for humans, are usually biased by the recording technique, and are grossly under sampled. Because of these and other constraints model simulations play an essential role in this field. For this reason, I believe that it is of great importance to advocate a rigorous validation culture.

| Verification | Validation |

|---|---|

| Verification is the substantiation that a computerized model represents a conceptual model within specified limits of accuracy. (SCS, 1979) | Validation is the substantiation that a computerized model within its domain of applicability possesses a satisfactory range of accuracy consistent with the intended application of the model. (SCS, 1979) |

| Verification is the process of evaluating the products of a software development phase to provide assurance that they meet the requirements defined for them by the previous phase. (IEEE, 1979) | Validation is the process of testing a computer program and evaluating the results to ensure compliance with specific requirements. (IEEE, 1979) |

| Verification is the process of determining that a model implementation accurately represents the developer’s conceptual description of the model and the solution to the model. (AIAA, 1998) | Validation is the process of determining the degree to which a model is an accurate representation of the real world from the perspective of the intended uses of the model. (AIAA, 1998) |

| Verification is defined as ensuring that the computer programming and implementation of the conceptual model is correct. (Sargent, 2013) | Validation is defined as determining that the model’s output behavior has sufficient accuracy for the model’s intended purpose over the domain of the model’s intended applicability. (Sargent, 2013) |

| Validation is the process of determining that the model on which the simulation is based is an acceptably accurate representation of reality. (Giannasi et al., 2001) | |

| Validation is the process of establishing confidence in the usefulness of a model. (Coyle, 1977) |

SCS: Society for Modeling and Simulation International

IEEE: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

AIAA: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics